Incense is an important aspect of Japanese culture that dates back nearly 1,500 years. Greater Japan was introduced to incense by Zen Buddhists, who used it at their temples during ceremonies and prayer.

According to legend, it is said that a log of agarwood washed upon the shores of Awaji Island during the Asukura Period in 595 CE. This log was then presented to Prince Shōtoku and Empress Suiko, who found the smell incredibly pleasing. Both the prince and the princess were already familiar with incense due to its introduction in 538 CE through Buddhism. At this time, incense was being imported from China through Korea, shortly after which, a ritual known as sonaekō became established. In this ritual, a collection of aromatic wood and herbs called koboku would be burned for religious purposes.

By the end of the Nara Period (710-794 CE), incense had become popular amongst courtiers and Japanese aristocracy. They were inspired by the use of incense during Buddhist rituals and began using it to perfume and cleanse their homes. Upper class Japanese people also began to also use the incense to perfume their hair and clothes, as this was a sign of refinement and good taste. The incense used was not one that most people would recognize today; instead of the sticks and cones today’s users are accustomed to, this incense was made by kneading the raw materials into balls.

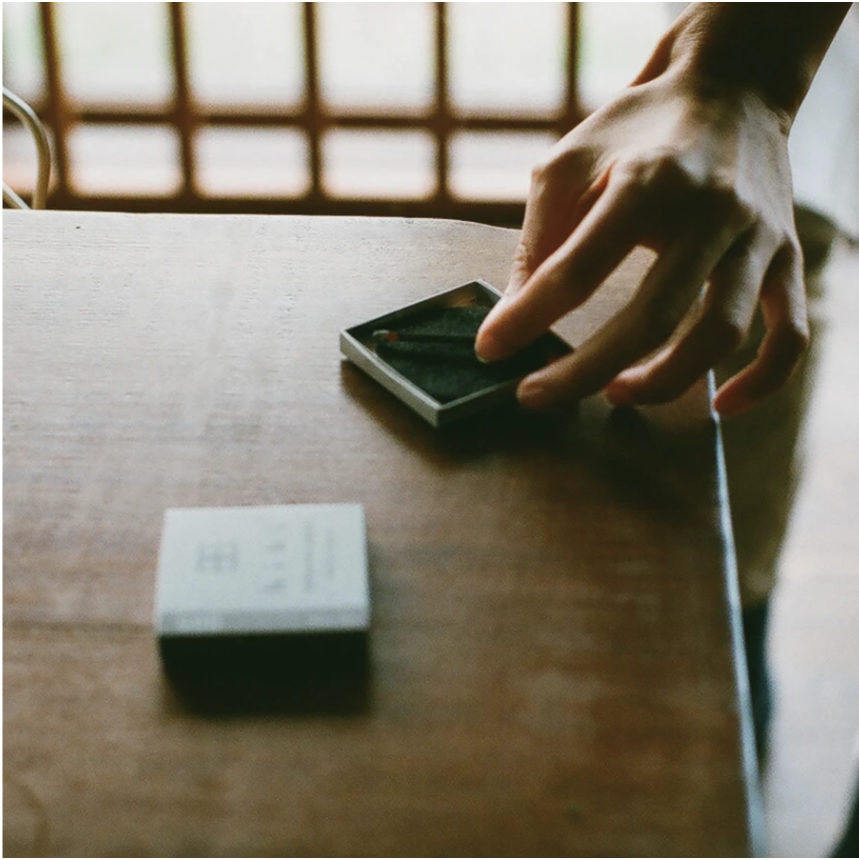

During the Heian Period (794-1185 CE), the use of incense grew in popularity. In the Japanese epic The Tale of Genji, we learn more about how incense was used and packaged. Most often, a large lacquer box was used to carry the incense and its supplies. There would be one outer box that contained several smaller boxes, each of which would hold the raw incense materials (aloe, clove, sandalwood, deer musk, amber, and herbs), in addition to small spatulas used to properly mix the materials.

After the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate in the 12th century CE, a new approach to Buddhism was introduced and the religion was popularized across Japan. This “New Buddhism” heavily favored the use of incense in its practice. This increased popularity of incense burning led to more informal incense gatherings, in which guests took turns enjoying 10 different incenses. These “incense games” were particularly popular amongst aristocratic warriors, where they would use wood incense sticks more akin to what we use today, rather than the aforementioned rolled incense.

During the Muromachi Period (1336-1573), Kōdō or “The Way of Fragrance” (香道) was introduced. Much like the Japanese Tea Ceremony (chadō; 茶道), this artform described the formal conduct in which to appreciate incense in Japanese society. Kōdō is considered to be one of three classical Japanese arts of refinement: kōdō, chadō, and kadō or "Way of Flowers" (華道).

Approximately halfway through the Edo Period, wealthy merchants began to buy incense allowing for the popular “incense games” to become even more widespread. Incense became a staple of society and was included in art, poetry, and fashion. Incense games were depicted in wood block prints, and the use of incense imagery became increasingly popular on decorative crests and kimonos. More incense tools were introduced, such as Japanese incense burners (kōro) and incense holders for perfuming hair, rooms, and clothes, along with several different types of boxes to store the incense wood.

During the Meiji Reforms (1867-1868 CE), there was a massive Westernization of Japan and the use of incense became passé. However, in the 1890’s, it slowly became more popular in Japan as embracing traditional Japanese culture became more acceptable again.

Today, traditional Japanese incense is used worldwide and is possibly more popular than ever. While there are still a number of brands, such as Nippon Kodo Incense, that keep the ancient customs of crafting and enjoying incense alive, many new and modern ways of enjoying incense have grown in popularity in recent times.